Part One: My History with Cohost and the Mastodon Furry Conspiracy

In 2016, shortly after Donald Trump won the US presidential election, I joined what was, at the time, a tiny social media network called Mastodon. I became very involved in the development discord doing a lot of "soft skills" labor like mediating conflicts, community relations, organizing the github, organizing and facilitating volunteer work, writing accessible copy, etc. and I came to be seen as quite important even though I never held any official status besides "girl who has extra permissions on the Github repository." I even used to individually welcome every new user I saw and provide them with tips on how to use the site, given that it was not very user friendly at the time. Mastodon is now gigantic, and memory of my early involvement has (perhaps fortunately) faded from the fediverse culture as time has passed.

Another early Mastodon user was Jae Kaplan, who ran a very small briefly active Mastodon instance called gay.crime.team. I actually had an account on that instance, though I was not active on it. I can't even remember what the conflict was, but at one point Jae had written something fair but critical about Mastodon's development "team" (all of whom were unofficial unpaid unrecognized volunteers except for Eugen Rochko) and I had responded with a long upset reply about how we are all queer unpaid volunteers and would it be so much to offer us a little good faith, or something like that. Jae subposted me by saying that "at least on Twitter, Jack doesn't jump into your mentions when you complain" (or something like that) and I posted "I'm not Jack" and then Jae left Mastodon forever and we were decidedly not friends. Not long after, I had a fight with Eugen and quit Mastodon development. Whenever I come up, he downplays my involvement, but if you ask anyone else who was volunteering at the time, they will confirm my side of the story. This was all in early 2017. I want to make this very clear, Jae Kaplan used Mastodon for less than half a year.

In 2018, I met Jess Levine, someone who I now consider to be my sister, and we became quite close. She was (and is) extremely popular on Twitter, and she influenced me into becoming more of an active Twitter user. Prior to 2018, I was very much a small fish. I had 300 followers on Twitter, and was only a big deal on Mastodon because I was an early adopter and Mastodon was tiny. Because of Jess, I began gaining followers who also had a lot of followers, and my tweets frequently began to "blow up." Over three years, I went from having 300 followers to 3,500 followers. I became "your favorite poster's favorite poster" and when I wrote a thread, it consistently got tens of thousands of retweets, likes, and comments. I was a twitter user who was only popular because I was in a clique with other popular twitter users. I wrote poetry, but nobody was following me because of my poetry. People just liked my opinions and how I wrote them, that was it. I became mutuals with famous writers who I respected, and gained recognition from people who I had looked up to since I was a teenager. It felt amazing. I felt powerful. I frequently compared my follower count to communities of people who had bullied me in my past. I had over 15 times more followers than the cult had members! I had twice as many followers as my undergraduate alma mater had students! It went to my head, let's say.

Jess was—and is—very good friends with Jae Kaplan, and had been for a very long time. She did not like that we did not like each other, and insisted we would actually really like each other if it weren't for what happened on Mastodon. During the Days of Awe in 2018, I DM'd Jae Kaplan on Twitter and apologized for my behavior in 2017. I was needlessly defensive and combative and Jae was just expressing a normal frustration and did not need to be put on blast like that. My aggression was unwarranted and from a place of stress that was not Jae's fault, etc. Jae accepted my apology in a very heartfelt way. Though, we still did not become friends.

In 2019, I visited Philadelphia to attend Jess's Passover seder. Jae and I were both staying at her house overnight for the seder, and Jess seated us together for the seder. Jess was right, we got along really well, exchanged privs, and became good friends. In 2023, we were in Jess's wedding party together. But in 2019, we were new friends, and Jae started sharing whispers of a "secret project" that was taking shape. Also in 2019, I started dating a Mastodon instance admin who lived in my state.

In 2020, the Anti Software Software Club released their manifesto. Also, you know, the COVID-19 pandemic went global, lockdowns, etc. and we all became even more extremely online. Jae talked excitedly in private about their secret project, which was originally something else, and then became code-named Fourth Website.

I hate having to talk about this, but another thing happened in 2020. I permanently left Mastodon due to an already toxic culture becoming even more toxic, and my then-partner's Mastodon instance was razed to the ground dramatically—only at-the-time the latest in a constant string of instances meeting similar fates. The events surrounding this spawned a sort-of anti-fandom whose members went so far as to do things like get a literal permanent butt tattoo to memorialize successfully driving me and my then-partner off of Mastodon. They did far worse things than that, but I feel like that is the only thing I really have to share for you to get the picture. This anti-fandom would later try to connect these events to Cohost.

So, to clear the air: Not Jae Kaplan nor anyone in Anti-Software Software Club circa 2020 was ever a member of my then-partner's Mastodon instance—nor were they active Mastodon users on any instance. People who were on that instance were followed around online across platforms for a while being accused of race-faking and having problematic fetishes, but nobody was doing that to ASSC at the time, because they had no connection to anything that was going on and nobody even really knew that Jae and I were friends.

After 2020, Twitter was my only social media. Jae would sometimes ask me things about Mastodon, or tell me excitedly about design ideas for Fourth Website, and it was always exciting but didn't take up much space in my head. I was an essential worker in the height of the pandemic, and I had bigger things on my mind.

In 2021, rumors started circulating that Elon Musk would buy Twitter. In 2022, he began and completed that process over a string of months that felt like forever. I was filled with dread. The idea of still using Twitter when it was owned by Elon Musk made my skin crawl. Seeing everyone talk about leaving Twitter made me panic. I had this whole platform on Twitter for my thoughts and opinions. My Twitter was a social safety net for me, in case I ever needed to do a GoFundMe. Twitter was how I stayed in touch with friends. Just the thought of not using Twitter anymore, and the app dying, made me so afraid and horrible feeling—so much like I would be dying. I realized I had an unhealthy relationship to Twitter.

ASSC seized the opportunity to get Cohost going ahead of schedule. I was invited to participate in the bare-bone "Friends and Family Phase" with only 100 alpha-testers on a site that took minutes to load each page and barely let you interact with each other. At first, it felt more like role-playing a social media website than actually using social media. We were playing pretend. Our most popular posts were parodies of common posts you'd see on other websites. Everyone was a friend of someone in ASSC, so we were only a couple degrees removed from each other socially. It was very culturally and socially homogeneous, and that is always going to be a problem with indie alternative online communities during their infancy. A lot of the problems that Cohost did have stemmed from the fact that this seed user base was homogeneous, but I also struggle to imagine what could have been done instead given the circumstances.

The friends and family phase members were given ten invite codes each to distribute in the beta phase. I invited my family first. Tom and Tom; and my then-polycule. While they were Mastodon early adopters, the Toms were never members of my ex's Mastodon instance. My old polycule was the only connection to that Mastodon instance, given that one member had been the server owner. Soon after this initial phase of invites, the people who were invited then got ten invite codes each, and that third wave of members is when a lot of former members of my ex's Mastodon instance ("snouts.online") joined Cohost.

When Cohost went public, I fully quit Twitter. I wrote about the benefits of quitting Twitter. I directed my 3,500 followers to find me on Cohost. Many of those followers used to be on my ex's Mastodon instance, because I was dating their former admin.

Cohost soon became public knowledge, and it was immediately beset by conspiracies and rumors that it was "Snouts 2." The anti-fandom from Mastodon spread outright lies and rumors about ASSC staff, claimed that Cohost was founded by former Snouts users (false!), and all sorts of misinformation not worth repeating. Bad actors joined the site in droves to harass people in the comments on posts, make bad faith accusations about ASSC staff, and generally be a nuisance. The lady who got a butt tattoo even showed up. There was a general sentiment of "We killed Snouts through the power of posting, and now we will kill Cohost for sport." These rumors spread quite far. I would tell people who never used Mastodon about Cohost, and how they should join, and they would say they heard bad things about it. "I heard it was run by pedophiles" was the most common. I should not have to explain to you the problematic history of accusing trans women of being pedophiles. Is now a good time to mention that the primary leader of this hate mob is, last I heard, a cisgender heterosexual white man who works in tech?

His hobby is harassing LGBT people online and accusing them of being fascists and pedophiles. He can posture as a leftist, but that is an embarrassing and childish way to spend your time.

These people persisted to slander Cohost and ASSC for the entire lifetime of Cohost and cheered the announcement of Cohost's financial failure in 2024. They apparently have nothing better to do than stalk me and my ex to other websites for sport. So I am putting this in my eulogy to clear the air.

The only big rumor I am aware of that is unrelated to my ex-polycule's anti-fandom was the fervor started by Dreamwidth's co-founder over a technicality in the TOS that ASSC addressed to my own personal satisfaction. But, you know, Jae is my friend, so I trust Jae, and thus am not concerned about that sort of thing as much as others might be.

This is not to say that Cohost was flawless. Far from it. I will get to that, as all extremely online millennial eulogies are mandated to tell you how problematic the demised was in life, lest you be accused of doing apologia for the dead. But the biggest most extreme stuff that you heard was 95% because some people online were really weird about my ex and I's relationship. I am sure that wherever I make a future home online will also be beset with rumors that the trans people running it are nazi fetishists and other such nonsense. It is honestly pathetic. You are only alive for an average of seventy-five years. Is this really what you want to spend it on?

With that out of the way.

Part Two: Cohost Was Good For Me

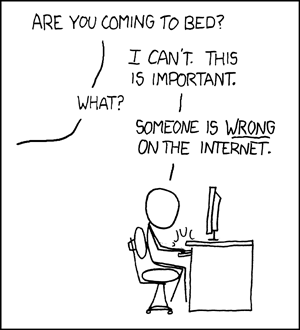

A common sentiment expressed since the announcement that Cohost is closing down has been "Cohost fixed me after Twitter broke me." I will echo this sentiment. Twitter gave me mental illnesses I didn't have before. Cohost felt like waking up from a dream. It is difficult to even remember all of the wild things I used to perceive as being of incredible importance. Anarchists versus Marxist-Leninists? Bisexual Lesbian Discourse? While these conversations aren't completely without merit, they are not worth receiving death threats over, nor losing sleep. Hypothetical intellectual conversations on Twitter felt like battles for your life and it gave me incredible anxiety. Being wrong could cost you your following, your sense of community, and whatever sense of power or safety they brought you. It did not matter what you were wrong about. When I moved over to Cohost, and stopped using Twitter, all of that dissipated rapidly. Who cares if somebody has an opinion that is wrong?

Something else happened when I switched to Cohost. I stopped merely posting and started writing. I never saw my twitter threads as substantial meaningful writing. They were tweets. There was a character limit I flaunted by going on and on. People replied before they finished reading. Every tweet had to be a fully self-contained paragraph. There was no room for hedging your sentences or adding nuance. The composer did not lend itself to going back over what you wrote and editing it.

Cohost had no character limit. I blogged. I wrote essays. I began to take my writing more seriously and in doing so took myself more seriously as a writer. I took what I said more seriously, put in more effort to say it well and capture every nuance, to be more considerate, to really think of each piece as something that could last and be returned to and not just an ephemeral string of thoughts. I proofread and edited. Now, sources needed citing, which meant doing research. So I would actually start borrowing books at work to read for the sake of my next essay. Tweeting did not inspire me to stand up from my desk and walk over to the Dewey 300s to grab The Golden Gulag and read some theory—something that I did do while writing my essay on carceral logic.

People had to scroll to the bottom to comment, and had no character limit there either. So the responses I got were deep and thoughtful and engaging. I actually enjoyed being disagreed with, because I felt like I was being given good faith and argued with in compelling ways that could actually change my opinions, and at times my opinions did change. I learned from my comments and people wrote incredible additions when they reblogged my essays. I moved my best work over to this blog, but I could not save all of those incredible additions. There is no way to go through the list of shares on a Cohost post. This design decision had a cooling effect on conflict, but it does now make it difficult to save my favorite additions to my writing.

My writing improved substantially, and I gained more confidence. I came to actually understand and believe that I am quite good at writing non-fiction essays. People enjoy my writing and, on Cohost, would tell me that explicitly in ways I truly internalized. On short-form social media, I was wasting that talent in a format that left me little room to grow. I was merely reacting to fights, and attributed any positive response to being retweeted by Jess or to my early involvement in Mastodon. On Cohost, I had room to grow, and realized that people truly liked my writing. They told me so in very explicit language.

The people I followed and engaged with on Cohost were smart and mature. Some attributed this to the age demographics skewing older, and perhaps that is true, but I also think the community cultivated and encouraged trying your best to be smart and mature. I often saw people who were younger, or had not yet built up their confidence, attempt to write a long high-effort post and preface it with some comment about how it is their first time writing something like that and they are going to try their best to do a good job at it. Cohost encouraged and rewarded effort, as opposed to vitriol. Cohost rewarded writing passionately and at length about something that you think is interesting even if it is not of critical importance to the world. You would log onto Cohost and learn something new about deep-sea biology, city planning, obscure cameras, strange plants, or the history of a small country's brief socialist revolution. Sometimes, the topic was so niche and obscure, that you had never even heard of its higher-level category—and those posts were often my favorites. 5,000 words about how a specific kind of ski lift works and why they do not make them that way anymore. 5,000 words about why incest is so common in low-quality erotic visual novels (I did not even know that it was common in the first place! I am not a consumer of this genre.) Oh, and so very much discussion about talmud, the weekly parsha, and halakhah.

Even a lot of frequent critics of Cohost staff would give fair, moderated critiques, interlaced with assurances that they recognize the effort staff were putting in and the circumstances they were under, and that they wanted to see these improvements because they loved the community and wanted it to succeed. Cheap dunks and spiteful comments were, usually, kept to private accounts.

I mostly only used Cohost on my phone or iPad. I only really use desktop computers at work anymore. CSS crimes looked very fun and creative but half the time did not work for me. I did not mind since the rest of the content on Cohost was still remarkably creative. There was a strong sense of collaboration and appreciation for each other's art. Communities formed around game development, illustration, comics, music production, photography, retro web design, and writing. While Cohost has been in hospice, we have been seeing all the different types of creatives coming together to send-off Cohost through their own specializations. The musicians did a music jam of bittersweet party anthems. The artists drew eggbugs flying off over the horizon. The web developers made grande finale CSS crimes and guides to help the non-techies build new homes. Community organizers pulled together in-person regional meetups and built ways to stay in touch. Writers wrote long sappy eulogies. I have never seen so much of an outpouring of love for a website in its final days. It felt more like May in senior year of college than a crowd fleeing a burning building.

Being able to use Markdown, HTML, and CSS in posts allowed for a lot more flexibility and creativity even for those who are less technically inclined. I was able to format my Queer Exchange parody like real Facebook comments; make functioning tables that worked across device; organize a long list of links in a small amount of space; utilize bulleted lists, headings, quotes, and footnotes; and retain white space formatting in poetry.

The community on Cohost was also remarkably helpful about everything. Any time I had trouble formatting something, someone would always pop up with a solution. The first time I tried to post So, the world is ending to Cohost, people were quick to offer me solutions to retain the formatting. When I had trouble porting it to this blog, a user I had never spoken to before appeared with an entire web page ready-made and coded to solve my problem. I built this blog with the help of Cohost users who helped me diagnose DNS issues, fix style sheets, and find workable hosting solutions.

The helpfulness on Cohost extended to generosity. Cohost gained a reputation as a place where crowd-funders quickly met their goals. Sites like tumblr and twitter can sometimes be overwhelmingly inundated with posts begging for financial assistance, but on Cohost such posts often met their goals so quickly that the original poster would delete their post within hours, and so these types of posts never became overwhelming like on other websites. I am not disparaging people for digital panhandling, you do what you have to do to survive, it is just remarkable that the reason Cohost timelines had fewer of them is because people's needs were successfully being met through community support. I even saw someone—somewhat audaciously—fund-raise the down payment for a house on Cohost with moderate success.

This high click-through rate also extended to creative projects. Despite being a smaller community than Twitter, Tumblr, Bluesky, etc. independent creators often remarked that they received tremendously more sales through Cohost than any other platform. Even people with tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of Twitter and Instagram followers received more sales through Cohost referrals than on Twitter and Instagram combined. Authors on Cohost gained enough press to be published. Kickstarters met stretch goals. Indie games broke even and made a profit. Cohost was lucrative for creatives despite its size. This makes total sense when you truly think about it. We know that the Twitter algorithm suppresses posts with any off-site link. Modern social media is designed to keep you on the site. They make their money through selling advertisements. Of course they would not build a platform for you to just advertise your wares for free.

This may also in part be due to Cohost having bewilderingly strong search engine optimization. It was incredibly easy for a Cohost post to become the top search result for a term. Users played pranks on Google's AI summaries by abusing this privilege. Still, it meant that searches for things like "Lesbian science fiction TTRPG" were more likely to return a Cohost post before an instagram post. It also meant that our in-depth well-researched essays created dependable information on the web that could actually be found by non-chosters looking for that information. That is rare to find on the web these days.

Cohost provided a stable home for adult content creators, who in the age of SESTA-FOSTA have struggled to market themselves and safely turn a profit. Erotic visual novels and pornography were not just present but welcomed and celebrated as genuinely desirable parts of the community. Censorship has become increasingly prevalent in the United States, which thus extends that censorship to the entire internet. I believe that there is an important place in society for pornography, including the "weird stuff." Not only does censorship quickly become a slippery slope that moves on from pornography to LGBT content in general, but it is also worthwhile to have pornography! Not that everything is clean and morally excellent in the adult entertainment industry—absolutely not. But that is not because of pornography being what it is. Independent adult entertainment creators and studios do not have the same labor issues as the mainstream studios. Without Cohost, there are even fewer places online where adult content creators can host and market their materials and earn a livelihood. This especially impacts transgender women and disabled people, for whom independent creation of erotic content online is often a vital source of income living under an economy that can be hostile to us and our needs.

Cohost had excellent memes, by the way. The creativity, collaborative spirit, and willingness to put in effort often resulted in some of the most fresh and delightful memes I've seen in ages. One flaw in Mastodon was always that the userbase was not very funny or creative. Rarely did you see a funny Mastodon post shared as a screenshot to another social media network, discord server, groupchat, etc. Most people do not use 4chan, but you cannot deny that screenshots of 4chan posts still frequently circulate the whole web and inspire memes across websites. Mastodon rarely originated its own memes, only importing them from other websites. Cohost had an incredible assortment of original memes that were more than just catchphrases or references. Cohost meme culture originated music genres, such as Lovehonk, and a cast of original characters like eggbug, tagslug, Intern Secretary Eggbug, and New Garfield. Each iteration on the meme was high-effort and incredible to behold. Some of the microfiction that came out of the Omelas meme was truly beautiful and raised insightful philosophical questions. Some memes were impossible to replicate on other websites due to technical limitations. I regularly saw screenshots of Cohost posts reposted to discord servers, reddit, groupchats, tumblr, YouTube, and Twitter often by users who did not use Cohost and had never even heard of it. While not the best for recruitment and marketing, it was still a testament to how funny the community was. I even heard Cohost posts read aloud on podcasts.

Cohost was an earnest and genuine place. You could laugh and cry. You could be serious or sappy. There was no need to couch anything in an aloof pretense of distance or irony; but nor was there a lack of self-awareness or a pressure to be cheerful. The full breadth of emotions were welcome. I felt comfortable opening up about things I wouldn't have on other platforms. I did not fear that failing to toe a line would result in death threats or ostracism. It felt personal and intimate, yet also a place with healthy boundaries.

Cohost was non-addictive. It felt like a nicotine patch for social media addicts needing to ween ourselves off. The lack of numbers and pagination removed that skinnerbox effect that trapped users in infinite scrolling on other websites. I could check a couple pages of Cohost and feel comfortable closing it. Do you remember the PBS Kids show Zoom produced out of WGHB in Cambridge, Massachusetts? Their slogan was "If you like what you see, turn off the TV, and do it." It was all about teaching kids fun activities they could do with their parents or friends. Cohost sometimes felt like that. Like I'd read some incredible long Cohost post and feel inspired to put my phone down and read a book that was mentioned, or go for a walk. Cohost routinely routed my attention and behavior away from my phone. Cohost slowed you down. You could not refresh your feed over and over to get new posts. Your read your feed a bit, and would not see anything new for a few hours at least. It was not that the website was dead or inactive, but that people created new posts slower, they put in effort, so there were just fewer new posts happening moment to moment. The good stuff would be reshared over and over, and while you could hide a post you'd seen before, the result was often just recognizing that you could read this one good post everyone loves and then log off.

Cohost did not have doomscrolling. We discussed politics and current events, but only on a daily basis—never second by second. There was no illusion that looking at Cohost would somehow change the world. Cohost did not feel morally important to look at. News you received from Cohost was at the frequency of a newspaper, not live updates. I cannot overstate how much healthier this was for me. I said this before in my essay on how to read the newspaper legally for free but unless you are second-to-second involved in something, you do not need second-to-second updates on it. Daily updates will suffice for nearly all current events happening outside of your own city which do not involve a loved one.

Cohost prompted personal reflection, introspection, contemplation of tricky and difficult questions, and then logging off and doing something in your life. There was a meme about Cohost inspiring people to unionize their workplace. I am not sure how many unions were actually started this way, but there was a common sentiment that Cohost inspired people to do activism instead of talk about activism. Cohost inspired people to change how they relate to each other and to their offline communities. Cohost inspired people to take serious actions to improve their mental health. Cohost inspired people to go find local offline meetups for their hobbies and interests. Several people lately have said that Cohost saved their life. While anywhere is important if you spend enough time there, it is clear that a lot of people received the communal support, encouragement, and financial bailouts they needed through Cohost.

Cohost had a tremendously positive impact on its users and the world around them. It did not become financially sustainable, but it succeeded at doing something good for the time it was here.

When I was moving the writing I was most proud of from Cohost to this blog, I was shocked to discover that over two years—including the half-year when I really did not write much due to suffering a traumatic head injury—I had written over seventy essays that I felt proud of and wanted to preserve. Cohost encouraged that kind of thing. People worked harder on themselves and their creative works. We were inspired by each other, and we grew.

Part Three: Learning from the Flaws

Cohost was very demographically homogeneous. Some people said that it was dominated by tech workers, and in my experience this was not true. My timeline rarely had tech stuff on it and most people I followed were not tech workers. My timeline was mostly illustrators and writers. Tech was not the homogeneous trait, race was. While Cohost was full of trans people, they were mostly white trans people. No census of any sort was ever performed, and the more restricted discoverability did make it hard to see the whole website at once. After all, if users did not tag posts with tags you happened to know to follow, you could never encounter an entire sub-community at all. Still, it was pretty felt that Cohost was predominantly white.

I think it's notable that even the critiques about racism on Cohost still take moments to say that Cohost was "better than other websites," but that bar is pretty low and I don't feel like we should be patting ourselves on the back for being "less racist." Some of the things I saw white users say on there were pretty shameful and prompted me to write a few posts essentially scolding the community and trying to teach other white people to not say something so stupid. I did not save these posts to this blog because I felt that without the context of what was happening on Cohost in that moment, they weren't particularly insightful or interesting. It was such basic "don't be racist 101" type content that I always felt a bit ashamed to find it necessary to write such posts for a community that was generally a lot more intelligent and mature than other places online. Like, did I really need to tell a website full of left-wing people not to put their white guilt on the shoulders of random strangers of color?

The community was not a monolith. The people who I followed were intelligent and mature, but the website was (in)famously 95% Autistic and the social skills were often lacking in some areas. As much as I praise the community, there were also a lot of outright stupid and immature people on there. That is probably unavoidable for any website with open sign-ups, but in such a small community their presence could be quite felt—especially when they are sending horrible anonymous messages to users of color telling them that someone anonymous was going to kill themselves due to the white guilt inspired by BIPOC online writing about the history of racism. We have no idea how many users were sending those messages, or if it was just one weirdo with a racist vendetta, but it was painful to see and I could only imagine how distressing and awful it must have been to be on the receiving end of such messages. The way I saw some users of color put it, was that it could sometimes feel more painful to experience racist microaggressions on Cohost because all the white users on Cohost were constantly talking about how wonderful our Cohost experience was, and so being the only ones receiving harassment like that created this sense of "why don't I get to have this nice peaceful experience too?"

I sometimes received inappropriate comments on my posts, though nothing bigoted. Usually they were oversharing, immature, or parasocial. On Cohost, it felt pretty easy for me to shut them down with a short targeted comment calling out the exact problem with what they were saying, and often that person would cease their behavior, or just block me and then I would no longer have to deal with them. I somewhat infamously had a user tell me that having me disagree with them was making them feel suicidal, and I told them unsympathetically that if someone disagreeing with them online is making them feel suicidal then they should log off and go take care of themselves because that is entirely the byproduct of their own mental health struggles and not something I am inflicting upon them. I considered what they were doing emotional manipulation and I was not going to humor it. I shut it down and I was right to do that—but I got blocked by a number of people who did not like me handling that user that way, and then my perception of Cohost from then on excluded those users. Many of those users were then the ones who were the source of other problems later, and I was confused because everyone was talking about something racist or stupid being said by a user who had blocked me already—so I did not see it until it came to someone posting screenshots.

A lot of the problems Cohost had can be traced to the Friends and Family Era. Not that the problems existed during that era, but that the website was rolled out that way. The first 100 users invited the next 1000 users who invited the next 10,000 users. So the first 11,100 users were all only a couple degrees removed from each other socially, and thus never more than three degrees removed from the ASSC staff socially. Anyone who joined Cohost was most likely to follow someone among the first 100 to 11,100 users, and thus people who were friends with ASSC staff, or friends of their friends, were the most influential and well-known people on Cohost.

We live, unfortunately, in a racially stratified and segregated world. People always tend to know more people of their own racial group and socioeconomic bracket than otherwise—and the exceptions are generally transracial adoptees, mixed heritage, or in a multiracial relationship. Society is set up to primarily expose you to others of your same demographics through neighborhood segregation, socioeconomic systems that affect who has access to higher education, racial and class discrepancies across professions due to hiring discrimination and education-related gatekeeping, and community spaces organized predominantly by one racial group tending to feel less welcoming to those of other groups.

Systemic racism and racial microaggressions keep BIPOC out of white spaces, and then white people know fewer BIPOC. Knowing fewer people of a demographic leads to ignorance and unconscious prejudice—especially when family and mass media raise you to perceive them negatively. It's harder to treat someone normally if you almost never talk to people like them. Even in Singapore, where the government enforces racial integration through authoritarian measures, their own government propaganda can only honestly claim that 30% of the Chinese majority have a close friend who is of the indigenous Malay minority. This is considered a victory by the Singaporean government in getting different racial groups to exist in community together.

Similar studies in the United States found that on average, a white American's friendship network is 90% white; and 67% of white americans exclusively have white friends. This was a big improvement compared to the last time these numbers were taken in 2013. I won't pretend that my own friendship network is color-blind cast, but I do beat the 90% white average at least. Other racial demographics have similar numbers, with the same study finding that Black Americans on average have 78% Black friendship networks, with 46% only having Black friends; Latine Americans on average have 63% Latine friendship networks with 37% only having Latine friends; and Asian Americans on average have 65% Asian friendship networks, with 31% only having Asian friends.

So when a small group of white people invite only their friends to join a new community space, it is statistically likely that the community space will be 90% white to start. That makes it very hard for it to become more racially diverse later. When those 100 seed users were asked to invite 10 friends each to join, 90 of those people were statistically likely to invite 9 white people and 1 person of color. When that new group of 100 people were asked to invite ten friends each to join—given that 90 of them were probably white and so probably 90% of those people's friends were white—it is statistically likely that they overall invited 7,290 white people and 2,710 people of color. This snowballing method of user invitiation, optimistically, was statistically likely to result in a userbase that is 74.5% white. However, a user being invited does not mean they actually joined. I mentioned above that the first people I invited were my family and partners, which I think is a fair thing for me to have done, with my remaining invite codes I tried to make an effort to invite BIPOC friends of mine, remembering what happened with Mastodon, but many of them did not join or did not remain for long. They joined a site that was 90% white and politely told me "Hey Shel, thanks for the invitation, but I don't think this website is for me." We never did a census, but I think Cohost ended up being more than 74.5% white.

People will join community spaces where people similar to them already exist. Once a space is predominantly white and homogeneous, it is incredibly challenging to get BIPOC to want to join and stay en masse. Cultural differences that appear invisible and innocuous to white people will feel alienating and hostile to others.

No amount of white people trying very hard to "not be white" is ever going to make a predominantly white space not feel white. Mastodon's attempts to "not be white" resulted in a weird toxic culture that tokenized BIPOC to the extreme and resulted in many white users who postured as "BIPOC-adjacent" to criticize other white users for being white. The white pot callingt the white kettle white and glueing themselves to any BIPOC who they can frame as agreeing with them. The minority of BIPOC in your community will not feel more welcome because you tokenize them and put them on a pedestal. The incredible pressure that puts on them makes the community space not a very fun place to be in. I have experienced tokenization for being a trans woman in a predominantly cisgender space and I did not enjoy the way it made me feel like I had to be perfect because I represented all trans people. I can only imagine how much harder it must be when you are someone whose racial demographic has been dehumanized and criminalized for centuries.

Cohost could have been more racially diverse from the beginning if, I suppose, there had been more of a concerted effort to create a more diverse seed population. However, I have a hard time imagining how one would do that and still get a socially coherent community with a small number of people. ASSC used their friends for alpha testing because their friends would get along with each other and be patient while the site was still being developed. It bootstrapped a sense of community, rather than 100 strangers with little in common. I think it is possible to find creative solutions to this problem, but there is not an obvious better way to have done it. Perhaps instead of giving the first 100 users 10 invite codes each, there was first an attempt to invite specific racially diverse online communities who may be looking for a new home? "I humbly invite you to create a new online space together, based on these values, which you could help shape and make your own. We admire your passion and creativity, and hope that our planned features would further enable that creativity." Cohost did have some active efforts to recruit NSFW content creators like this, so perhaps future similar projects could prioritize racial diversity in those efforts.

Without an effort to shape the seed population to be more racially diverse, then the other option would have been a large number of BIPOC joining the platform together (who probably already knew each other) and choosing to stay despite the overwhelming white majority of the existing community and despite the racist microaggresions they experienced. I have observed that once a community space has a critical mass of a given minority group, then people from that group will feel comfortable and join in droves. Word of mouth spreads through the above-mentioned racially-determined friendship networks. Once a predominantly cis space has enough trans people, it will double the number of trans people quickly. This could have been possible with BIPOC communities on Cohost, I suppose, but it did not happen.

White people are, historically, bad at building racially diverse communities. It's nothing special that ASSC was no better. If only white people make it, then mostly white people will join it. Communities become more diverse when they become more diverse. If you want to build a racially diverse community, you need to build the space with a racially diverse coalition. That is the only thing I have ever seen succeed. Even if the invitation strategy was attempted, it would require BIPOC to trust some random white people. I think it is obvious why a lot of BIPOC are not inclined to trust random white people.

Even in Philadelphia, one of the most racially diverse places in the entire world, communities and organizations tend to be predominantly of a single racial group—whether it be white, Black, asian, or latine. It is striking how often local Black friends will attend an event organized by white people in a city that is predominantly Black and say that they were the only Black person there—and then will reference some other event of a similar nature organized by Black people and I'll have never heard of it.

People's social networks tend to be racially homogeneous with only small points of overlap. This is due to systemic factors, not personal failings. We exist in the context of all in which we live and what came before us, even on the internet. It is harder to meet people of other racial groups in a racially stratified society. People grow up in racially homogeneous neighborhoods, attend racially homogeneous schools, internalize unconscious prejudice, and don't develop the social skills around how to behave in a multicultural environment. White people historically divide everyone into "white" and "not white" and our parents, grandparents, and great grandparents intentionally moved into all-white communities in America, so even "post-integration," the places we grow up tend to be very predominantly white with some Asian families and like, one Black family. The not-white communities tend to be more diverse, but there is still segregation. Most people in American grew up in a neighborhood dominated by their own ethnic group. Segregated neighborhoods that are over 90% Black are incredibly common. You can't undo a history of segregation just by saying that it is now legal for people to live in mixed-race neighborhoods.

Experiencing racism makes BIPOC not exactly eager to befriend white people either—even if the majority of white people were more eager to form those friendships. Encouraging multiracial communities is one of the problems of sociology and social psychology; and if there were an easy solution you know that Singapore would have implemented it already. It does not help that members of the privileged racial majority group often do not want to be in a multiracial community and will actively fight you on your integration efforts. If you invite your friends to kick-start your new space, and your friends are all the same race as you, it will be hard to get other people to join. Even BIPOC in your space will hesitate to invite more BIPOC into your space if it is predominantly white. It's hard to invite someone into a space where you know they will feel alienated and possibly experience racist microaggressions.

This is not to do apologia for the racism that was experienced on Cohost or its homogeneity, but rather to highlight the lesson to be learned. This is a systemic issue at the societal level which Cohost was one manifestation of. If you want to prevent this same issue from recurring in whatever other community you're trying to create, then you must proactively take efforts to build a racially diverse community from the beginning and it will not be easy to keep it that way. You cannot achieve a racially diverse community that is free of racism by simply "not being racist." Racial harmony does not exist in the absence of active racism, it must be built and created. The internet is a microcosm of the real world offline. It is not a martian habitat dome isolated from the lives we live outside of it. Telling users you will ban them for being racist does not stop BIPOC in your community from experiencing racism. Even if the moderation on Cohost had been quicker to respond to racist microaggresions, that would still only have been a reactive strategy and would not prevent future racist microaggresions. ASSC staff did a poor job at quickly reacting to these incidents, but it would take proactive efforts to prevent them. There is not a ready-made proven successful proactive strategy for preventing racism and we should not act like there is one. Life would be so much easier if we could just give white people the anti-racism spiel that removes unconscious bias, conscious prejudice, and ignorance like it's the ending of the Barbie movie and they're deprogramming the stepford barbies. I think the snowballing method of recruitment may have been naive, and it is something I will learn from and think about in future community organizing efforts.

The other issue that arose from the Friends and Family Era was that having a community where the most well-known users are all friends with the leadership did make us all rather defensive—especially after we were raided by my ex's anti-fandom from Mastodon. I said earlier that Cohost did not usually have cheap dunks, but the exception to that is when people were critical of Cohost and its staff. I am personal friends with Jae Kaplan and so I trust ASSC staff implicitly and have faith in their efforts. When people criticized ASSC staff, they were criticizing my close friend, and I—among other early adopters—got defensive of them. I sometimes acted the same way I did when Jae criticized Mastodon's development. I sometimes wrote long careful essays defending them, either directly or indirectly. Given how many of Cohost's critics were bad faith actors from Mastodon, it was easy to dismiss any critic as just being a hater we could tell to shove it.

This behavior from the friends-and-family era users was, understandably, quite off-putting to people who were not friends with ASSC staff. Sometimes, an earnest good faith critique was met with nasty hostility. This got so bad at one point that ASSC staff had to make a post asking people to stop white knighting for them. The "player versus player" zones of Cohost were the comments section on any staff post. Fortunately, the comments being attached to those posts did contain the conflict in a place you could choose not to look.

Sometimes, friends-and-family users would respond to critics with "Cohost is not for everyone" which was intended to mean "to each their own taste of platform" but I think this often came off as "Cohost is not a welcoming inclusive place for all kinds of people." Especially once there was the context of racist microaggressions, people stopped saying this. It looked bad.

The lesson to learn, I think, is similar to the lesson to take from the racial homogeneity issue. When you create a new community that you want to be welcoming to a diversity of people, try to seed that community with people who are different from yourself. Recruit some total strangers. I do not know how to do this ideally, but that is the takeaway I have. If you start a community from just your own friends, then you will get a community that is homogeneous and not the most welcoming to newcomers who do not already share a culture or subculture with you.

Part Four: I don't want to go

It's telling that a tremendous number of Cohost users are choosing to create independent blogs rather than return to short-form micro-blogging. Some users are trying to create entire new online communities. There is nowhere else on the internet quite like Cohost and we don't want to go anywhere worse. The old social media was bad for us and Cohost felt good to use. Even many of the users who were the most critical of Cohost are, in its final days, writing eulogies expressing that there was no better social media website they'd rather use and they are not going to return to Twitter or Bluesky. There is a new indie blogosphere and newsletter-sphere... being born from Cohost's ashes, because we just don't want to be addicted to numbers again. A lot of people are using Bear Blog, which looks super cute and all but it actually has more numbers than the platform I'm using (Ghost) and I'm not as much of a fan of the web 1.0 aesthetics as others are. I might make a more private Bear blog just for friends and more personal life updates, but my high effort writing will be living here.

Cohost is just the latest community space I am losing this year. My old synagogue has decided to systematically exclude disabled people in a way that made me feel really unwelcome and gross, my brain injury has left me with too little energy to stay involved in union organizing right now, Twitter is dead, and the Great Unmasking makes most other community spaces I could join quite difficult to participate in fully. My life is gradually becoming more solitary and less connected. While I hope that my readers will keep up with my writing on here, there is far less likelihood of my writing being able to reach as much of an audience as it used to. I have set up Ghost to Zapier to Buffer to Twitter integration so when I post on this blog, it automatically shares it to my old Twitter without me having to look at Twitter. I may make a Bluesky account that does the same. It won't be the same as having an engaged and interested community of people.

I am sad and depressed. I am depressed for a lot of reasons. I wrote down every reason that I am sad, graphed them out, drew connections between them, and tallied up the connections. Then, I ranked them. Whatever has the most connections would be both the product of my problems and something that, if alleviated, would alleviated all of my problems. Cohost is one of 14 things I am sad about. The one with the most connections is simply that I am lonely. COVID-19 makes me lonely. The Great Unmasking makes me lonely. Burnout makes me lonely. The effects of my concussion make me lonely. Cohost shutting down makes me lonely. I will be lonelier when it is gone. I will be lonelier in a way I was not when I left Mastodon or Twitter. I will have lost something, without gaining as much where I go next.

I am working on this issue in therapy, now. I treat my therapy appointments like meetings where I create tasks for myself and track progress towards goals. I am looking into local events and ways to make more local friends and community. I organized the Cohost Wake which I hope will be something that results in people bringing their Cohost relationships offline into friendships that last. I am doing things to alleviate the problem.

Still, the depression dulls the feelings. I have cried quite a few times lately but it is hard to say if it is about Cohost or my other 13 problems. It does not feel real that it is going away. All the tributes have been giving me feelings. It is bittersweet. We will move on. I have another forty-five years of my life ahead of me. Already, people are mobilizing to organize new communities in new places. I am sure when it happens I will see a lot of the same familiar faces there who joined Mastodon in 2016 and flock to every indie alternative social media network. Maybe next time it will be more diverse and less tokenizing. Maybe next time we will be even more patient and kind. Maybe next time, the mascot will be a little cocoon, and after that network goes away, the one we build after that can be a moth-themed community and we can make memes about eating clothes.

This change also coincides with a big change in my professional life. I have had a very special project close to my heart that I have been working on for two years, and right as I am wrapping it up and tying a bow on it, I have been offered a promotion to a completely different kind of position that would take me away from this passion project. My work would shift from being focused on LGBT issues to Disability issues, which feels appropriate to how my life has been going. I would no longer be managing collections of physical books, and instead mostly be working with audiobooks and braille books, which feels appropriate to how my brain injury has limited my ability to read print books and is leading me to depend more and more on audiobooks. Maybe I can learn to read braille and have a non-audio form to read print books again.

What I have gained from Cohost is that I am now much more passionate about my writing and creative endeavors. I have gained a healthier relationship to myself, other people, politics, the news, and so much more. I grew and healed. For all of its faults, I truly believe Cohost was more good than it was bad, by a substantial factor.

Thank you Jae, Colin, Aidan, and Kara—for making such a wonderful website.

Thank you Cohost, everyone who was a part of Cohost, for giving me such a meaningful and wonderful experience.

I'll still be blogging. So subscribe to my newsletter, or the RSS feed. The same account you make for the newsletter also lets you comment on posts! Please leave comments it is the only way I know that you are reading these and enjoying them. Please share your thoughts on my writing, your additions and disagreements, it is what I will miss most about Cohost.

Thank you Clastic Artist for letting me use your art as my header for this post.